by Peter Prokosch

We must conclude a „peace agreement with nature“ was the call from UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in his opening speech for the UN World Conference on Nature (COP15 CBD). Since Monday, December 19, reaching this goal no longer seems unrealistic. In Montreal, the delegates from the 196 member states of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted a new „Global Biodiversity Framework“ (GBF). The new global nature treaty is intended to regulate the protection and sustainable use of the Earth’s biological diversity for the coming years. The agreement contains 23 targets to put nature on a path to recovery by 2030. In concrete terms, the community of states commits, among other things, to place at least 30 per cent of the planet’s land and marine area under adequate protection by 2030. In addition, renaturation measures are to be initiated on 30 per cent of the damaged ecosystems by 2030. Protecting 30 per cent of the planet is considered the most crucial measure to stop the loss of species and ecosystems. This so-called 30×30 target is equally essential for our future as the climate protection agreement from Paris in 2015 to keep global warming under 1,5%.

Norway, with the EU and around a hundred other countries, had long supported the 30×30 target and campaigned for it. Now, as this world-important decision is reached, it is high time to focus on the implementation at home. So far, and outside Svalbard, there are hardly any convincing examples of large-scale protection of natural areas in Norway. The country’s „national parks“ barely meet international standards and have weaker protection than many developing countries. Norway is notably lagging behind in the protection of marine areas. Recently, representatives of the Norwegian Marine Research Institute described the Norwegian marine protected areas as „paper parks“ and pointed out the gap between international declarations and domestic actions.

No Norwegian national parks have given nature the „right of self-determination“, where significant parts of the area can develop freely without human interference. „Let nature be nature“ is an unknown term in Norway. Fishing and hunting are allowed almost everywhere. Even the vulnerable and (on a European scale) unique wild reindeer population in Hardangervidda National Park is hunted. In addition, sheep farming is carried out in the same area, which brings diseases and makes it difficult to allow a natural predator population on the plains. If one would stop sheep farming and hunting and instead open up for large predators, many of the problems the wild reindeer population has today would disappear. Outside the national park, habitats are fragmented by human encroachment. Tourists contribute to the problem of demanding any physical infrastructure at the cost of nature and just because the reindeer herds do not dare to come close to them and their paths. In a scenario where the animals are not hunted, they would eventually no longer, to the same extent, be so afraid of humans and could thus use areas they now avoid because of the mountain walkers. The predators will take over the hunters‘ function of „managing“ the population. They will take out sick and weak animals and prevent diseases from spreading. By turning Hardangervidda into a full-fledged national park, the reindeer will fare better, and those who hike in the mountains will have the opportunity to see the animals up close. There are also significant economic opportunities here for the local tourism industry, which will offer a unique wilderness experience in fantastic nature.

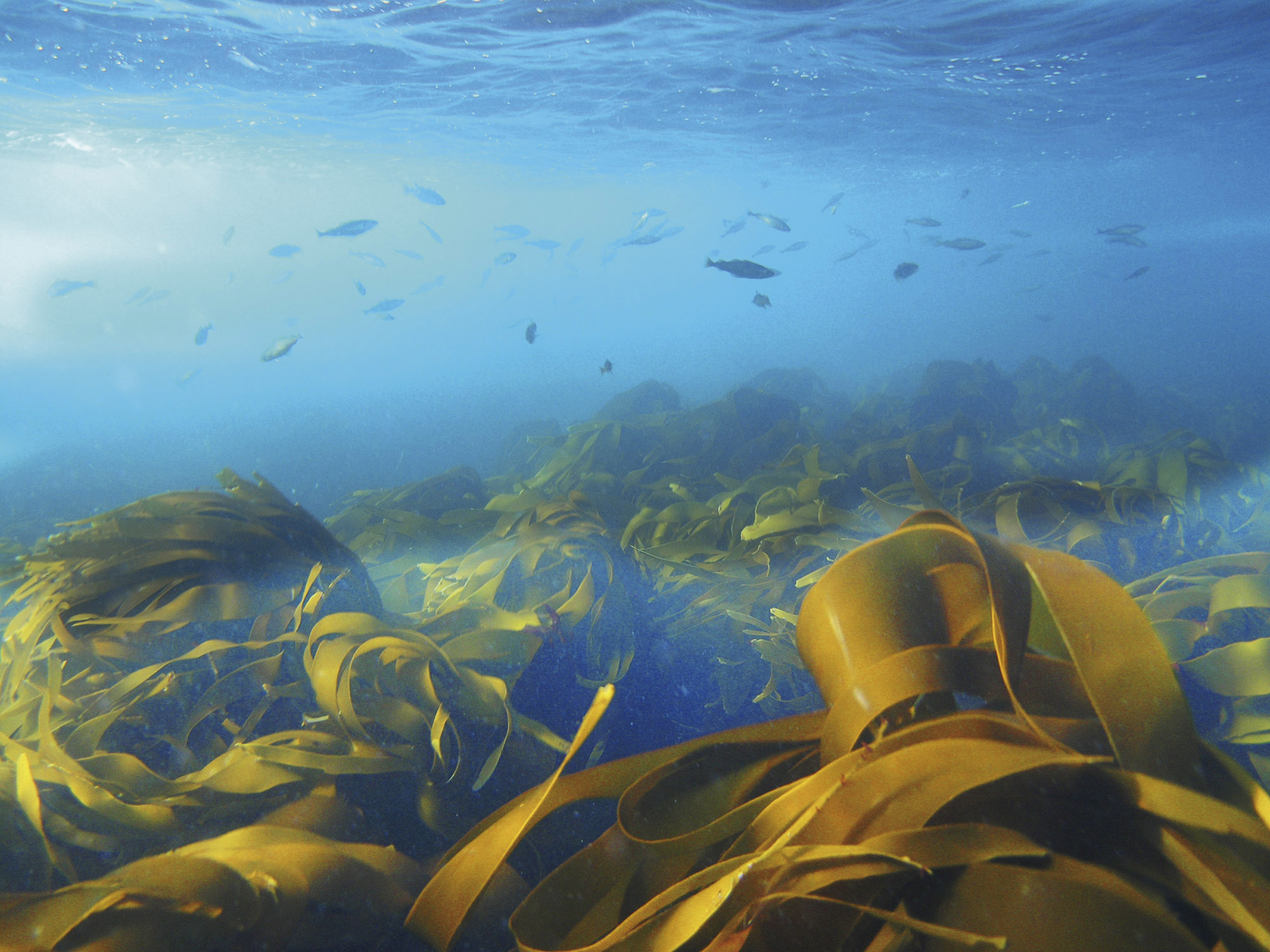

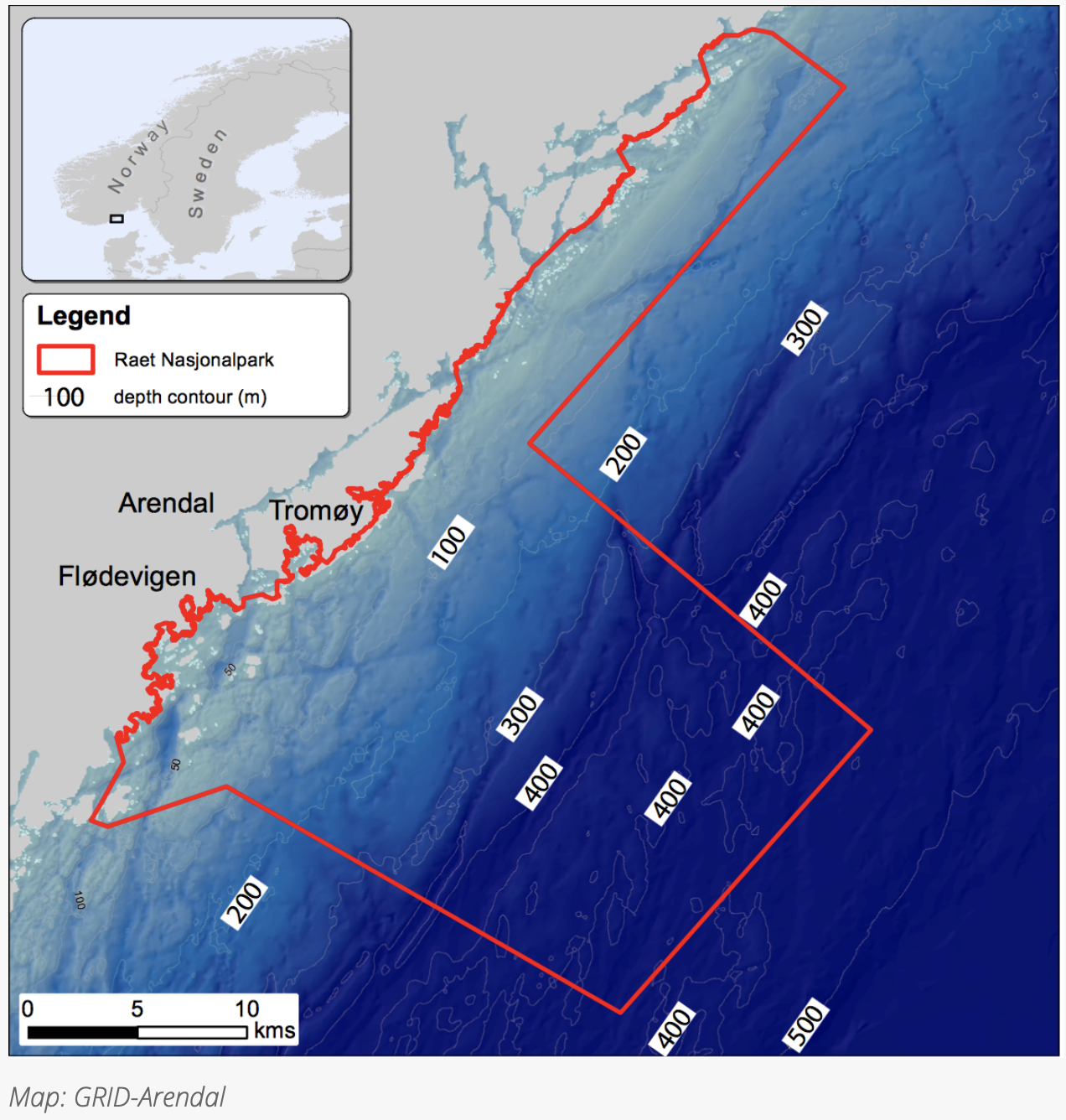

Another area with great potential if large no-take zones were implemented is „Raet“, Norway’s largest marine national park. The 607 km2 park is managed by the three municipalities of Tvedestrand, Arendal and Grimstad. Divers and marine biologists have removed vast amounts of fishing equipment from the seabed, raising awareness about the lack of real protected zones. The scale of the littering of the seabed has been thought-provoking for the National Park Board and may lead to requesting improvements of the park. Many have also experienced the positive effects of the lobster reserve and the no-fishing zone that Tvedestrand has established in the nearby sea area.

Raet National Park is a local recreation area and an attractive area to holiday in. The tourism industry benefits from preserving the natural values in the area. Representatives from the tourism industry, together with other stakeholders, can provide support for the establishment of large no-fishing zones and other conservation measures. Raet can become the „finest“ national park in Norway. It means, e.g. a no-take zone of at least 300 km2 covering all habitats from the coast to the deep sea and no hunting of birds and marine mammals in the entire national park. It should not be difficult to achieve this in collaboration with local authorities and research environments such as the Marine Research Institute laboratory at Flødevigen or GRID-Arendal.

Suppose Raet becomes the first national park in Norway where natural processes can go undisturbed without human intervention, such as hunting and with large protected areas for fish, mammals and birds. In that case, Raet can become a model for other national parks in Norway and gain international recognition.

The Montreal decisions at COP15 CBD of a new „Global Biodiversity Framework“, including the 30×30 goal, can be seen as a huge Christmas present to the entire world. It should be a significant incentive for all governments to implement those goals now in their countries. In particular, for the rich countries in the North, such as Norway, it should be an obligation to come up with the best examples of large-scale protected areas and to support countries in the global South to replicate them. The tourism industry, which often advertises and benefits from wild nature, could also set positive examples at home by campaigning for real national parks for a „peace agreement with nature“.