The fishing nation Chile obviously is on the way to become a leading country when it comes to establishing marine protected areas (MPAs), inclusive huge no-fishing zones. As e.g. the Smithsonian magazine wrote already in February, Chile’s President Michelle Bachelet signed into law protections for nearly 450,000 square miles of sea. This equals about 1,16 million square kilometers, similar to the size of France, Germany and the UK together. Environmental NGOs such as WCS or the Pew Foundation highlighted Chile as well and had played a role in this achievement. It will be interesting to assess also the role of tourism and what still needs to be done to achieve the SDG-target 14.5 equal to the CBD-“Aichi target 11” to protect gglobally10% of the sea and coasts by 2020.

The fishing nation Chile obviously is on the way to become a leading country when it comes to establishing marine protected areas (MPAs), inclusive huge no-fishing zones. As e.g. the Smithsonian magazine wrote already in February, Chile’s President Michelle Bachelet signed into law protections for nearly 450,000 square miles of sea. This equals about 1,16 million square kilometers, similar to the size of France, Germany and the UK together. Environmental NGOs such as WCS or the Pew Foundation highlighted Chile as well and had played a role in this achievement. It will be interesting to assess also the role of tourism and what still needs to be done to achieve the SDG-target 14.5 equal to the CBD-“Aichi target 11” to protect gglobally10% of the sea and coasts by 2020.

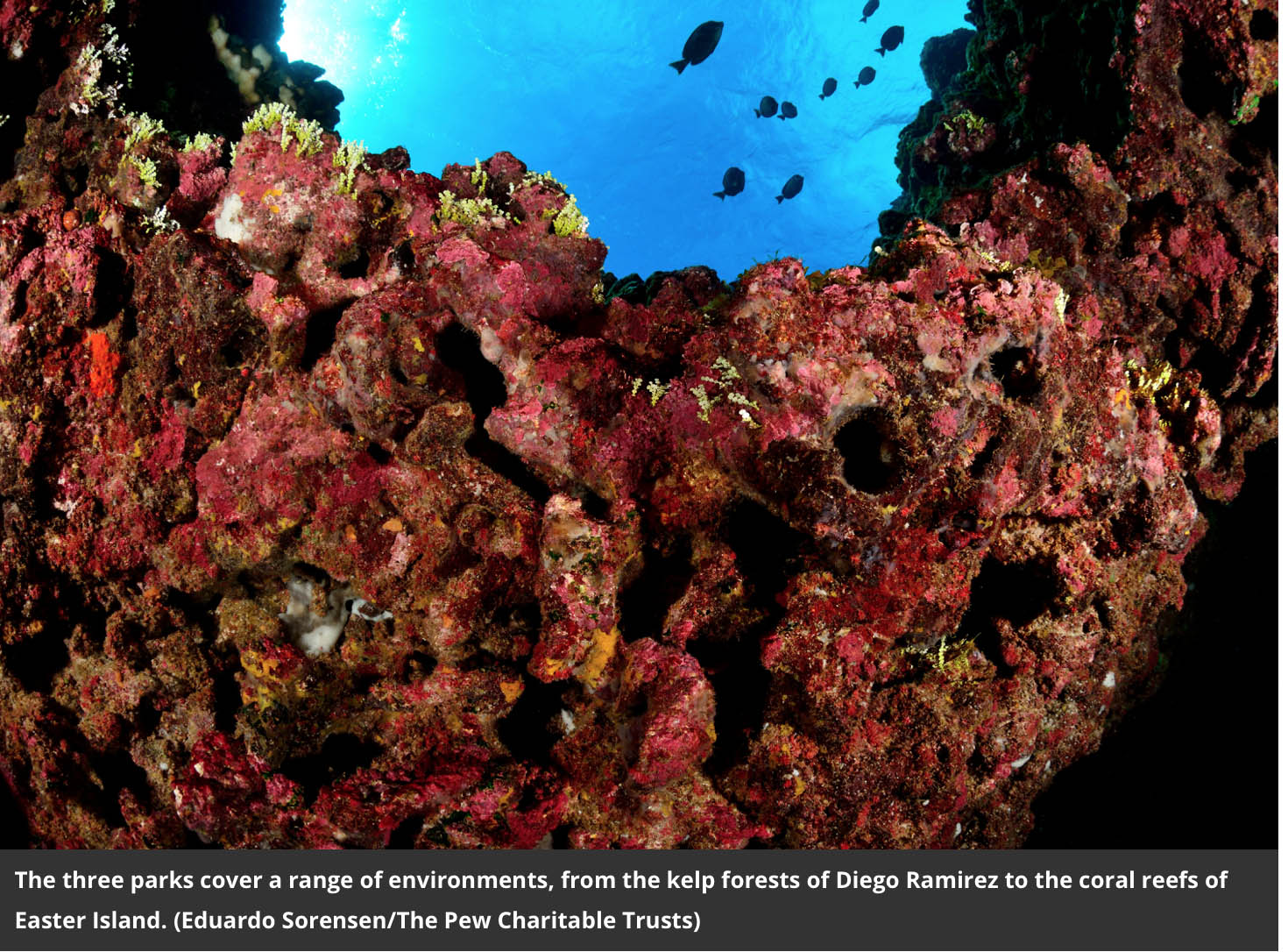

Read how Maya Wei-Haas started her article in the Smithsonian magazine, she wrote February 27, 2018: “Today, Chile’s President Michelle Bachelet signed into law protections for nearly 450,000 square miles of water—an area roughly the size of Texas, California and West Virginia combined. Split into three regions, the newly protected areas encompass a stunning range of marine environments, from the spawning grounds of fish to the migratory paths of humpback whales to the nesting grounds of seabirds.

“The Chilean government has really positioned itself as a global leader in ocean protection and conservation,” says Emily Owen, an officer with Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, which has worked for over six years to help make these protected waters a reality. With the new parks, more than 40 percent of Chilean waters have some level of legal protection.

“The Chilean government has really positioned itself as a global leader in ocean protection and conservation,” says Emily Owen, an officer with Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, which has worked for over six years to help make these protected waters a reality. With the new parks, more than 40 percent of Chilean waters have some level of legal protection.

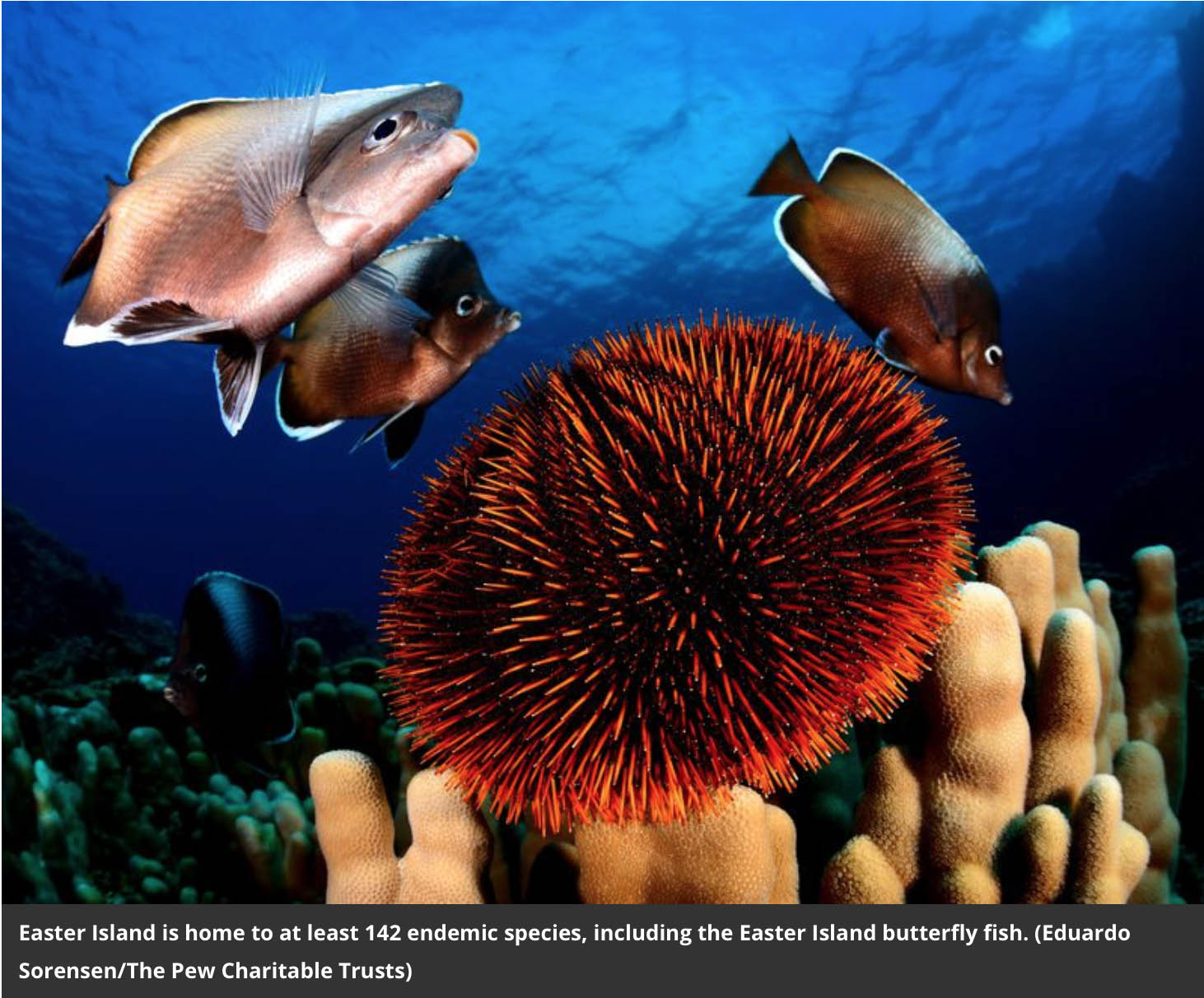

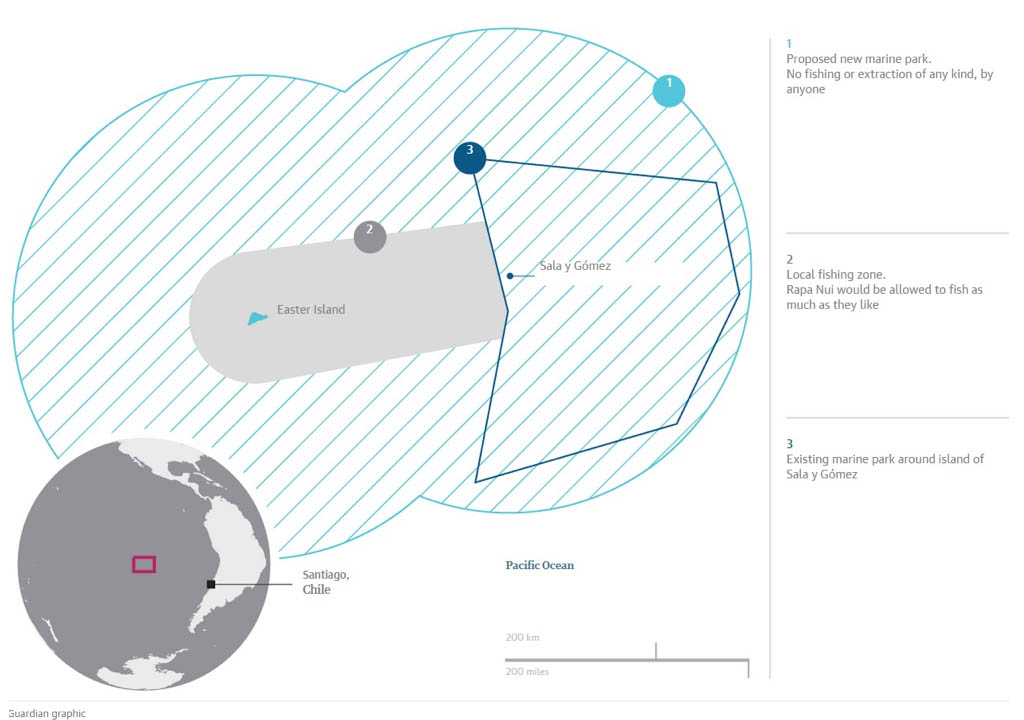

The largest of the three regions is the Rapa Nui Marine Protected Area (MPA), where industrial fishing and mining will be prohibited but traditional fishing remains permissible. At 278,000 square miles, this area encompasses the entirety of the economic zone of Easter Island, safeguarding more than 140 native species and 27 that are threatened or endangered. Notably, it is one of the few marine protected areas in the world in which indigenous people had a hand—and a vote—in establishing the boundaries and level of protection.

“I like to think of Easter Island as an oasis in the middle of an oceanic desert,” says Owen. The islands themselves are the peaks of an underwater ridge teeming with life. They also provide important spawning grounds for economically significant species like tuna, marlin and swordfish.

The second largest region is 101,000 square miles around Juan Fernández Islands, located some 400 miles offshore Santiago, Chile’s capital. Like Easter Island, these islands are also the peaks of lofty submarine mountains that rise from the deep ocean. But their slopes foster an unusual mix of tropical, subtropical and temperate marine life. All fishing and extraction of resources will be prohibited in this region, which boasts the highest known percentage of native species found in any marine environment. This area joins a small number of waters with complete protection: Only about 2 percent of the oceans are fully protected to date.

The second largest region is 101,000 square miles around Juan Fernández Islands, located some 400 miles offshore Santiago, Chile’s capital. Like Easter Island, these islands are also the peaks of lofty submarine mountains that rise from the deep ocean. But their slopes foster an unusual mix of tropical, subtropical and temperate marine life. All fishing and extraction of resources will be prohibited in this region, which boasts the highest known percentage of native species found in any marine environment. This area joins a small number of waters with complete protection: Only about 2 percent of the oceans are fully protected to date.

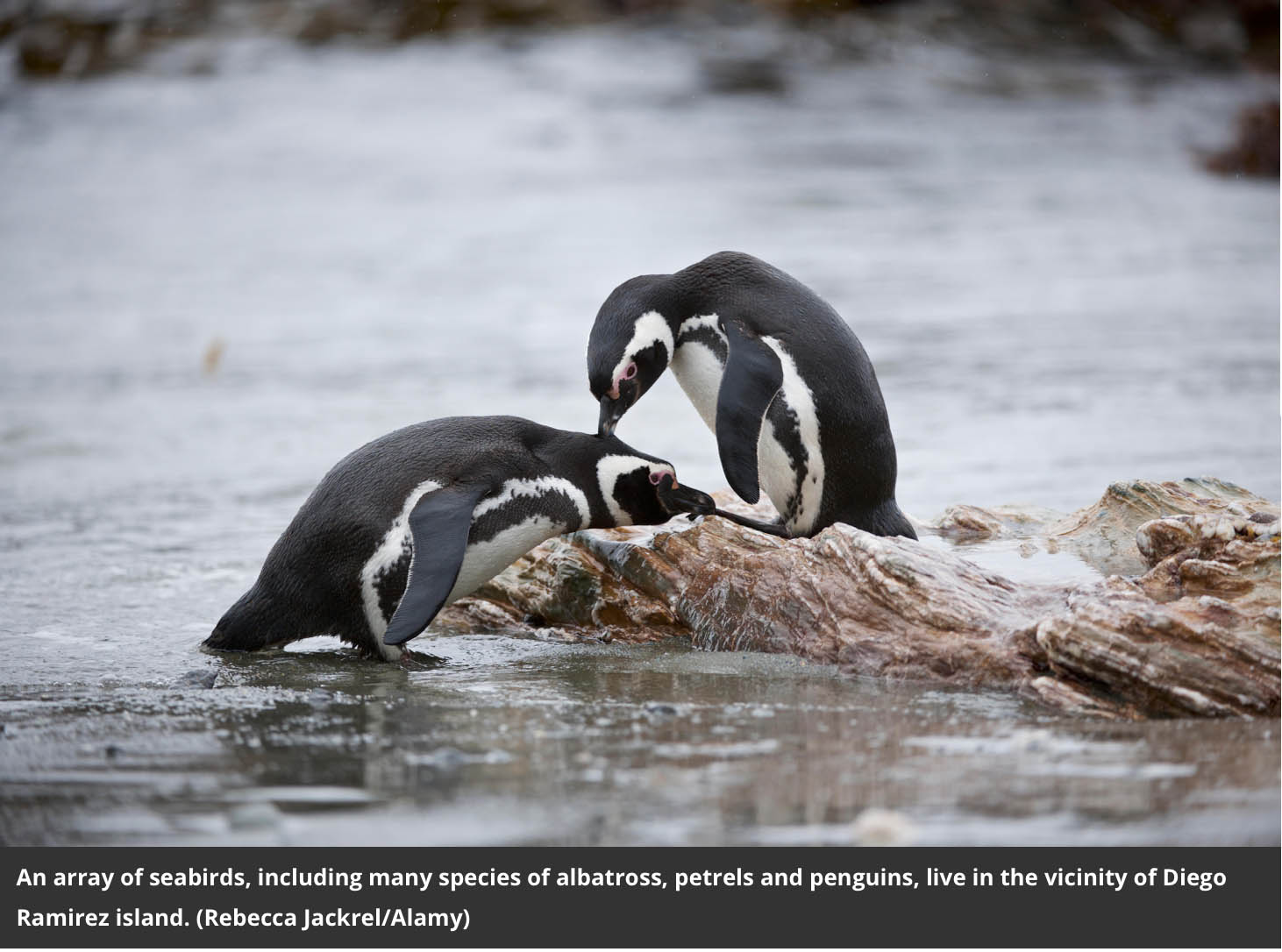

Finally, around 55,600 square miles of fully protected waters encompass the kelp forests of Diego Ramirez island, Chile’s southernmost point. Like the trees of a rainforest, the towering lines of kelp support a bustling underwater city and nursery for young sea

creatures. These massive photosynthesizers are also believed to lock away a significant fraction of the world’s carbon dioxide.

The Diego Ramirez waters are some of the last intact ecosystems just outside the  Antarctic region. “It’s really wild and pristine,” says Alex Muñoz, director for Latin America of Pristine Seas, an initiative from the National Geographic Society that provided scientific support for the creation of the Juan Fernández and Diego Ramirez protected regions.”

Antarctic region. “It’s really wild and pristine,” says Alex Muñoz, director for Latin America of Pristine Seas, an initiative from the National Geographic Society that provided scientific support for the creation of the Juan Fernández and Diego Ramirez protected regions.”

One of the players in this development has also been The Wildlife Conservation Society Marine Protected Area Fund (WCS MPA Fund). It is designed to assist countries to meet their U.N.-commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Sustainable Development Goal 14 to protect 10 percent of coastal and marine waters by 2020. The goal of the WCS MPA Fund is to invest a minimum of $15 million by 2020 to support legal declaration of new MPAs in 20 countries covering 3.7 million square  kilometers of previously unsecured and unprotected ocean. WCS will deploy funding to support scientific field staff personnel and partnerships with government and NGOs for establishing MPAs. Since the launch of the WCS MPA Fund in September 2016, and as of June 2017, WCS has initiated new MPAs in 19 countries, including: Fiji, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Bangladesh, Tanzania, Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Argentina, Belize, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, the U.S. and Canada.

kilometers of previously unsecured and unprotected ocean. WCS will deploy funding to support scientific field staff personnel and partnerships with government and NGOs for establishing MPAs. Since the launch of the WCS MPA Fund in September 2016, and as of June 2017, WCS has initiated new MPAs in 19 countries, including: Fiji, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Bangladesh, Tanzania, Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Argentina, Belize, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, the U.S. and Canada.

It will be interesting to see, how all these and other nations compete to set the best examples of well managed MPAs, and to assess, where tourism played a supportive role. This may also be on the agenda when the parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity are meeting at their CBD COP14 in November in Egypt. The member states will have to get prepared to work on their conclusions for 2020 how far the world will have achieved the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and what should be the new Biodiversity targets after 2020.

As LT&C understands itself as a support organization to achieve the CBD Aichi target 11 of a globally complete and well managed protected area network by 2020, by profiling examples, where tourism plays a positive role achieving this goal, we will have a close look at these outcomes.

As LT&C understands itself as a support organization to achieve the CBD Aichi target 11 of a globally complete and well managed protected area network by 2020, by profiling examples, where tourism plays a positive role achieving this goal, we will have a close look at these outcomes.