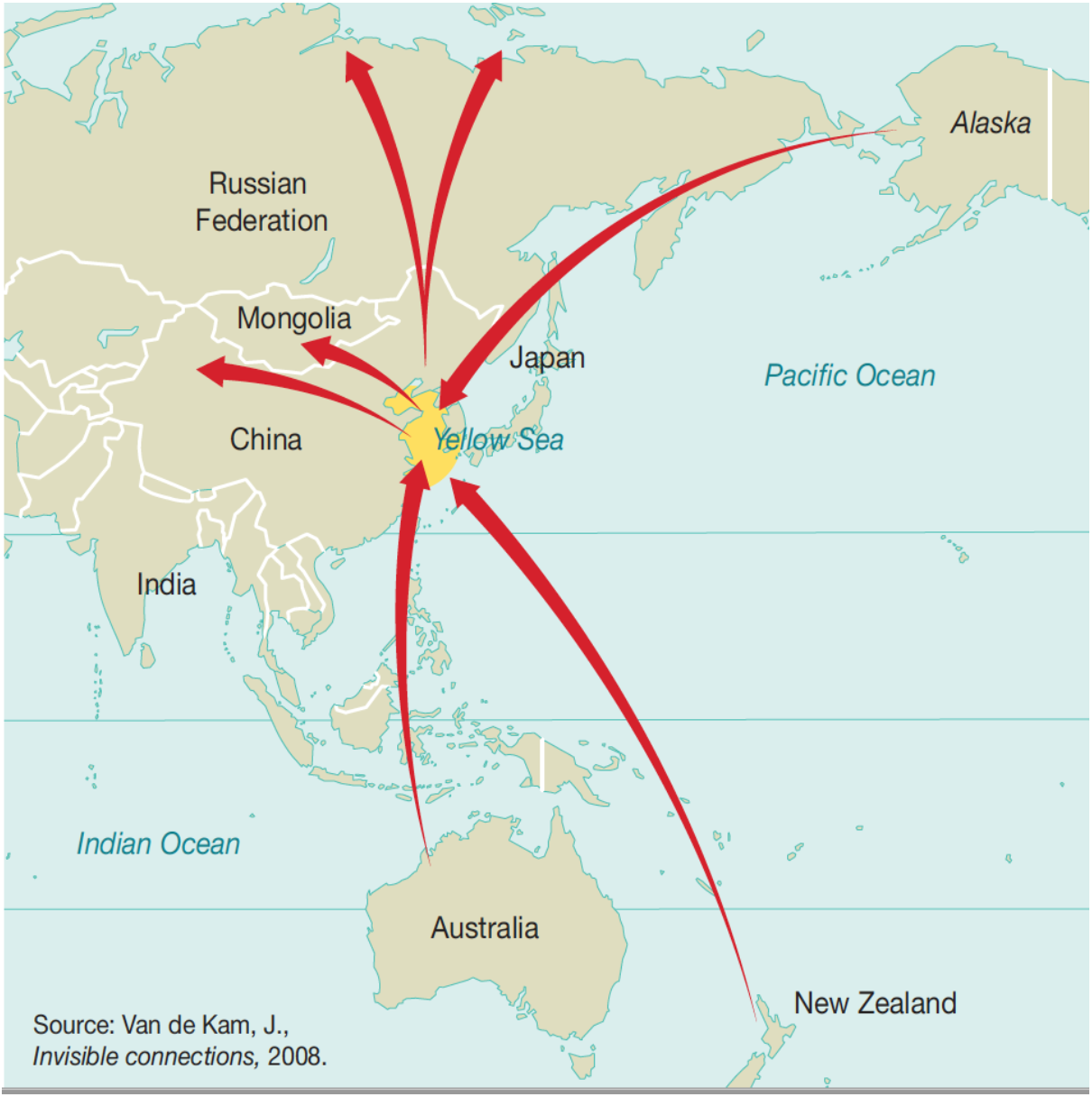

A great step towards the protection of the internationally important Yellow Sea tidal flats has been made earlier this year: the Chinese government announced that it will halt all ‘business-related’ land reclamation along its coast. This is an extremely valuable achievement, where among other bird watching travellers and also representatives of the LT&C-Example Wadden Sea (see also initiatives for trilateral World Heritage) are involved in. Every year millions of shorebirds migrate from the southern hemisphere, many from as far as Australia and New Zealand, to the Arctic to breed and back again. Nearly all are dependent on the food-rich intertidal mudflats of the Yellow Sea Ecoregion (the east coast of China and the west coasts of North and South Korea) as stopover sites. For those interested in this region, we herewith reproduce an article of Birders Beijing and recommend to subscribe to the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP) Newsletter.

A great step towards the protection of the internationally important Yellow Sea tidal flats has been made earlier this year: the Chinese government announced that it will halt all ‘business-related’ land reclamation along its coast. This is an extremely valuable achievement, where among other bird watching travellers and also representatives of the LT&C-Example Wadden Sea (see also initiatives for trilateral World Heritage) are involved in. Every year millions of shorebirds migrate from the southern hemisphere, many from as far as Australia and New Zealand, to the Arctic to breed and back again. Nearly all are dependent on the food-rich intertidal mudflats of the Yellow Sea Ecoregion (the east coast of China and the west coasts of North and South Korea) as stopover sites. For those interested in this region, we herewith reproduce an article of Birders Beijing and recommend to subscribe to the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP) Newsletter.

“It’s worth taking a moment to try to comprehend the endurance and resilience required by these birds, many of which are small enough to fit in the palm of a human hand. One population of BAR-TAILED GODWIT (Limosa lapponica) winters in New Zealand and flies, via the Yellow Sea, to Alaska and then, after raising its young, makes an 11,000 km nonstop return journey. The energy requirement for this flight is equivalent to that of a human running at 70 kilometres an hour, continuously, for more than seven days. Along the way, these birds burn up huge stores of fat—more than 50 percent of their body weight—that they gain before they set off, and they even shrink their digestive organs.

Sadly, the number of Bar-tailed Godwits successfully reaching New Zealand each autumn has more than halved, from around 155,000 in the mid-1990s to just 70,000 today. The Bar-tailed Godwit is just one of more than 30 species of shorebird that relies on the tidal mudflats of the Yellow Sea Ecoregion. The populations of most are in sharp decline, none more so than the charismatic but ‘Critically Endangered’ SPOON-BILLED SANDPIPER (Calidris pygmaea).

So, what is the reason for the decline? Scientists, including Prof Theunis Piersma and his team, have uncovered evidence for what many birders and conservationists have long suspected – that a major cause of the decline is the reclamation of tidal mudflats along the Yellow Sea. They’ve shown that birds using the Yellow Sea twice per year – for their spring and autumn migrations – are declining at a faster rate than those using the Yellow Sea only once. It’s a ‘smoking gun’.

Around 70% of the intertidal mudflats in this region have disappeared and much of the remaining 30% is under threat. If the current trajectory continues, the Yellow Sea will become a global epicentre for extinction.

However, in January, the Chinese government announced that it will halt all ‘business-related’ land reclamation along its coast. This is a massive boost to the tens of millions of migratory shorebirds along the East Asian Australasian Flyway (EAAF) that depend on the intertidal mudflats of China’s east coast, including species on the brink of extinction, such as the ‘Critically Endangered’ Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea) and the ‘Endangered’ Great Knot (Calidris tenuirostris).

Two English-language articles reporting the change in policy were published in the Chinese media – one on Xinhua, China’s largest news agency, and one in The China Daily. Significantly, the latter was posted on the website of the State Council, China’s ‘Cabinet’, indicating the high level of support for the new policy.

The articles reported on a 17 January 2018 press conference held by Lin Shanqing, Deputy Director of the State Oceanic Administration (SOA). Lin outlined several elements of the new policy:

First, the government plans to “nationalise reclaimed land with no structures built on it and will halt reclamation projects that have yet to be opened and are against national policies.”

Second, all structures built on illegally reclaimed land and that have “seriously damaged the marine environment” will be demolished.

Third, “the central government will stop approving property development plans based on land reclamation and will prohibit all reclamation activities unless they pertain to national key infrastructure, public welfare or national defence”.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly in terms of the future of China’s east coast, “local authorities will no longer have the power to approve reclamation projects”.

Gu Wu, head of SOA’s National Marine Inspection Office, said that

“in the past, land reclamation, to a certain extent, helped to boost economic development by mitigating the land shortage in coastal regions and providing space for public infrastructure and industry parks. However, illegal and irregular reclamation activities caused a number of problems to marine ecosystems and lawful businesses” and that “those effects have become a major public concern, so the administration decided that reclamation would be closely looked at in its annual inspection last year.”

The press conference on January 17th was preceded by two media articles criticising coastal provinces for their mismanagement of land reclamation projects, revealed by SOA’s 2017 inspections. Hebei Province (home to well-known birding sites such as Beidaihe, Nanpu and Happy Island) was admonished because “tourism, aquaculture and shipbuilding had all been allowed in a national nature reserve in Changli County.”

And Jiangsu (home to Rudong and Taozini) and Liaoning (home to Dandong and Dalian) were subject to finger-pointing in this article.

In Jiangsu Province:

- “a total of 14 projects, involving 81.29 hectares of reclaimed land”, had been wrongly approved since 2012;

- A large amount of reclaimed land remain deserted, with only 21.28 percent of reclaimed land actually developed;

- Developers of 184 land reclamation projects had not obtained government approval before they started building their projects; and

- The province was failing to effectively protect nature reserves. Fish farming had been operating in about 9,955 hectares of sea waters around a national wetland reserve in Jiangsu, where such commercial operations should have been banned.

And in Liaoning Province, the SOA found that:

- The provincial government was failing to effectively supervise land reclamation projects and control pollutants from being discharged into the sea;

- Although the provincial government fined polluters and violators of reclamation regulations, more than half of the fines had not been collected;

- Among 211 wastewater drains into the sea registered by the provincial environment authorities, 68 were not approved through legal procedure and some of the drains have not been carefully monitored.

SOA’s announcement of the new policy on land reclamation came as something of a (very welcome) surprise to the conservation community. However, those with experience of working in China will know that policy development often works in this way.. the process of policy formulation is opaque and when a new policy is announced it is not uncommon for the announcement to be the first information to emerge from the government that a policy review is taking place.

Of course, announcing a new policy is one thing; implementation is another. China’s record on implementing environmental regulations is not the best, as can be seen in the violations of existing regulations in Hebei, Liaoning and Jiangsu. It remains to be seen whether this policy will be enforced with the rigour required to ensure the integrity of the remaining intertidal mudflats. Nevertheless, at this stage, there is no reason to think that implementation will not happen. In fact, I am optimistic; the new policy is consistent with President Xi’s focus on building an ecological civilisation, as he emphasised at the 19th Communist Party Congress and it is in line with the recent strengthening of environmental regulations, including the Environmental Protection Law.

Halting land reclamation along China’s coast is a necessary but not sufficient step to slow the decline in populations of shorebirds of the East Asian Australasian Flyway. The priority will now be to ensure protection for, and effective management of, the key sites for migratory shorebirds. This is what organisations such as the East Asian Australasian Flyway Partnership, BirdLife International, the Paulson Institute and local NGOs will be focusing on over the next months and years.

Halting land reclamation along China’s coast is a necessary but not sufficient step to slow the decline in populations of shorebirds of the East Asian Australasian Flyway. The priority will now be to ensure protection for, and effective management of, the key sites for migratory shorebirds. This is what organisations such as the East Asian Australasian Flyway Partnership, BirdLife International, the Paulson Institute and local NGOs will be focusing on over the next months and years.

Transforming the fortunes of the world’s most threatened flyway will only be possible if there is cooperation between all of the countries along the route – from Russia in the north to Australia and New Zealand in the south. China’s role in the East Asian Australasian Flyway is key and could set an example for countries hosting the world’s other major flyways, including the Atlantic and Pacific Flyways which also face threats, such as pollution and habitat loss associated with the drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

While there is a huge amount still to do to ensure the future of migratory shorebirds in East Asia, China’s announcement could be the turning point for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper and the many other species dependent on the intertidal mudflats of the Yellow Sea coast. At this stage, it would be churlish to say anything other than “Well done, China”!

See also Living Planet: Connected Planet and the GRID-Arendal Photo Library